Megabats in Australia.

Aboriginal cave art of bats © Les Hall

Oldest in Australia

Australonycteris clarkae, from the Eocene of Queensland, is the oldest bat from the Southern Hemisphere and one of the oldest in the world. It is similar to other archaic Eocene bats from the Northern Hemisphere, and could probably navigate using echolocation, like most bats do today. Until its discovery, palaeontologists thought that bats colonised Australia much later, perhaps during the Oligocene. Australonycteris is only known from a single fossil site near the town of Murgon in southeastern Queensland. 20 cm wingspan. Eocene Epoch

(55 million years ago - 34 million years ago).

Grey-headed Megabat (Pteropus poliocephalus)

Vulnerable

Australia's only endemic flying-fox species. Occurs in the coastal belt from Rockhampton in central Queensland to Adelaide in South Australia.

Colour: The Grey-headed flying-fox has dark grey fur on the body, lighter grey fur on the head and russet/orange fur encircling the neck. It can be distinguished from other flying-foxes by the leg fur, which extends to the ankle.

Size: 23 cm to 29 cm (head and body length). Its wingspan is over one meter.

Call: more than 30 different calls that are associated with specific behaviours; for example, mating, locating its young, defending its territory, and squabbling over food.

Diet: They feed on the nectar and pollen of native trees, in particular Eucalyptus, Melaleuca and Banksia, and fruits of rainforest trees and vines. They lick nectar from flowers, collecting pollen on their fur; and crush fruit in their mouths, swallowing the juice and some of the fruit but spit the seeds out. They feed at night and prefer to eat close to where they roosts (resting upside down) but can travel more than 60 kilometres in search of food. individuals will defend their feeding territory, returning to the same feeding ground each night until the food source is depleted.

Habitat: Subtropical and temperate rainforests, tall sclerophyll forests and woodlands, heaths and swamps as well as urban gardens and cultivated fruit crops. Roosting camps are generally located within 20 km of a regular food source and are commonly found in gullies, close to water, in vegetation with a dense canopy. Recently Camps have tended to be located within 300m of water sources.

Movement: They spend the day roosting in groups known as camps, hanging upside-down from the branches of trees. They leave the camp at sunset to feed, returning in the early hours of the morning or at dawn. Grey-headed Flying-foxes show a regular pattern of seasonal movement with most of the population found within 200 km of the eastern coast of Australia, from Rockhampton in Queensland to Adelaide in South Australia. They move depending on the climate and the flowering and fruiting patterns of their food sources. In times of natural resource shortages, they may be found in unusual locations.

Breeding: Annual mating commences in January and continues over many months. Females give birth to a single live young in September to late November each year. The baby feeds on milk from it’s mother’s nipples for five to six months. The baby clings to its mother’s belly for the first three to six weeks, before being left in a crèche in the camp while its mother looks for food at night. When she returns, she recognises her baby by its call and possibly its smell. The baby progressively learns to fly in the camp from about three months old then begins to follow the adults each night, learning how to find its own food. The young are able to feed independently when five to six months old.

Federal Status

Australia: Listed as Vulnerable (Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Commonwealth): December 2001 List)

State Listing Status

NSW: Listed as Vulnerable (Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016 (New South Wales): April 2018 list)

South Australia: Listed as Rare (National Parks and Wildlife Act 1972 (South Australia): Rare Species: June 2011 list)

Victoria: as Threatened (Flora and Fauna Guarantee Act 1988 (Victoria): June 2017 list)

Non-statutory Listing Status

IUCN: Listed as Vulnerable (Global Status: IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: 2017.1 list)

Victoria: Listed as Vulnerable (Advisory List of Threatened Vertebrate Fauna in Victoria: 2013 list)

NGO: Listed as Vulnerable (The action plan for Australian mammals 2012)

Spectacled Megabat (Pteropus conspicillatus subsp. conspicillatus)

Vulnerable

Restricted to tropical rainforest areas between Ingham and Cooktown, and between the McIlwraith and Iron Ranges of Cape York

Restricted to tropical rainforest areas between Ingham and Cooktown, and between the McIlwraith and Iron Ranges of Cape York

Spectacled flying-foxes have the smallest known population of the four Australian mainland flying-foxes. The latest monitoring gives a population of less than 100,000 with calculated population figures of 75,347 in November 2016 (Westcott et. al. 2018) which represents a decline of over 75% from November 2004. The summer counts of Spectacled Flying-foxes suggest a maximum population size of less than 95,000.

Colour: Spectacled flying-foxes have distinctive straw-coloured fur around the eyes which gives them their name. Eye rings can sometimes be indistinct and they will look similar to black flying-foxes. Pale fur on shoulders can vary between individuals.

Size: Average weight 500–1000g

Head–body length 220–240mm

Diet: Spectacled Flying-foxes are specialist fruit eaters that feed mostly on rainforest fruits, favouring nectar and pollen of eucalypt blossoms. They also feed on other blossoms as well as native and introduced fruits.

Habitat: Spectacled Flying-foxes roost high on the branches of trees. They roost together in groups often made up of many thousands the largest camps are estimated around 20,000). Camps are often found in patches of rainforest and swamps as well as mangroves associated with black flying-foxes. They are only located in Coastal Queensland from Ingham to the tip of Cape York and islands in Torres Strait. A small camp is located in the Lockyer River area. The majority of the population is located in the Wet Tropics.

Movement: They only forage during the night, and can travel up to 40km from camp to feed (a total travel distance of up to 80km), with an average of 7km between feeding sites. They disperse seeds of at least 26 species of rainforest canopy trees, with 14 of these species only being dispersed through the action of Spectacled Flying-foxes.

Breeding: Mating is common throughout the first half of year but conception only in March–May, with single young born October–December. Mothers carry the young for 3–4 weeks. After this time, the young stay at the camp during the night until they start to fly.

Federal Status

Australia: Listed as Vulnerable (Environmental Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Commonwealth): May 2002 list)*

State Listing Status

Queensland: Listed as Vulnerable (Nature Conservation Act 1992 (Queensland): September 2017 list)

Non-statutory Listing Status

IUCN: Listed as Least Concern (Global Status: IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: 2017.1 list)

NGO: Listed as Near Threatened (CD) (The action plan for Australian mammals 2012)

*NOTE: Spectacled Flying-foxes are currently being considered to have their status uplisted to Endangered based on the significant population decline over the past 13 years.

Least concern

Colour: The black flying-fox is almost completely black in colour with only a slight rusty red-coloured collar and a light frosting of silvery grey on its belly.

It has no fur on its lower legs.Colour: The black flying-fox is almost completely black in colour with only a slight rusty red-coloured collar and a light frosting of silvery grey on its belly.

Size: It’s the largest species of Flying-fox in Australia ranging from 500-1000g. 23 – 28 cm (head and body length), with a wingspan of over one metre. Forearm length up to 19 cm.

Call: loud, high-pitched squabbling!

Diet: They prefer pollen and nectar from eucalypt blossoms, paperbarks and turpentine trees; however, they may also eat other native and introduced flowers and fruit, including mangoes, when native foods are scarce or during drought. They have also been seen feeding on leaves by chewing them, swallowing the liquid and then spitting out the fibre.

Habitat: Tropical and subtropical forests, and in woodlands. Forming camps in mangrove islands in river estuaries, paperbark forests, eucalypt forests and rainforests. Large communal day-time camps are found in mangroves, paperbark swamps or patches of rainforest, often with grey-headed flying-foxes. Occur around the northern coast of Australia (Western Australia, Northern Territory, Queensland and northern NSW) and inland wherever permanent water is found in rivers.

Movement: During the day they roost on tree branches in large groups known as camps. Main camps form during summer and their size varies depending on the availability of local food. They leave the camp at dusk to feed, finding food by sight and smell, and by following other bats. The groups can travel over 50 km to feed and will use the same camp for many years. Black flying-foxes are found in Northern and eastern Australia. They can fly at 35 – 40 kilometres per hour and may travel over 50 kilometres from their camp to a feeding area. They often share their camps with other flying-fox species.

Breeding: Mating occurs in autumn and the female gives birth in late winter or spring when food is abundant. The gather into large camps during spring and summer when their young is born. The young are carried by their mothers until they are about four weeks old when they are left at the roost while their mothers forage at night. They begin to fly at around 2 months but remain dependent on their mothers for at least three months.

CONSERVATION STATUS

Black Flying-foxes are vulnerable to loss of feeding areas from clearing of native vegetation and land degradation from agriculture. Black Flying-foxes are not currently threat-listed by the Commonwealth Government, or any State Government. As a native species, they are protected via each State or territories environmental legislation.

Least concern

Colour: Fur is red-brown and their wings more translucent. reddish brown-coloured fur.

Colour: Fur is red-brown and their wings more translucent. reddish brown-coloured fur.

Diet: Little Red Flying-foxes appear to favour the nectar and pollen of eucalypt blossom over other foods that make up their diet, such as other flowers and fruit. Orchards are raided sometimes when other food is limited. They feed almost entirely on blossom of eucalypts and melaleucas.

Habitat: Little Red Flying-foxes are known to hang out in many different habitats. They are highly nomadic, taking up camp wherever their favourite flowers and fruits are in season. The most widespread species of megabat in Australia, they fly further into inland Australia than other flying-fox species, following the flowering of eucalypts. They occupy a broad range of habitats found in northern and eastern Australia including Queensland, Northern Territory, Western Australia, New South Wales and Victoria.

Movement: Camps can contain hundreds of thousands to a million and roost closer together than other flying-foxes. Like Australia’s other flying-foxes, the little red flying-fox makes plenty of noise at night. A nocturnal feeder, they can be heard shrieking, squabbling over food or simply flying by, silent but for the beat of its wings. Using their jointed thumbs to climb, the little red flying-fox will clamber about trees while roosting or feeding.

Breeding:They breed at different times of year to the Grey-headed and Black Flying-fox, Little red flying-foxes give birth to one young per litter, usually in April to May, with mating occurring between November and January.

CONSERVATION STATUS

Little Red Flying-foxes are vulnerable to loss of feeding areas from forestry operations, clearing of native vegetation and land degradation from agriculture. Little Red Flying-foxes are not currently threat-listed by the Commonwealth Government, or any State Government. As a native species, they are protected via each State or territories environmental legislation.

Least concern

Eastern and north-eastern Queensland.

- Large-eared flying-fox (Pteropus macrotis subsp. epularius)

Least concern

The only known location of this species in Australia is a mangrove island beside Boigu Island, and Saibai Island (both within a few kilometres of the New Guinea coast).

iucnredlist.org

iucnredlist.org

- Christmas Island flying-fox Blyth's Flying Fox (Pteropus melanotus subsp. natalis)

VulnerableRestricted to Christmas Island

iucnredlist.org

- Bare-backed fruit bat (Dobsonia magna subsp. moluccensis)

??Most of north, north-central and east Cape York.

Atlas of Living Australia

Sources:

Hall, L. & G. Richards (2000). Flying foxes: Fruit and Blosson Bats of Australia. Sydney, NSW: University of NSW.

Van Dyck, S. & R. Strahan (2008). The Mammals of Australia, Third Edition. Sydney: Reed New Holland.

Megabats are large bats that feed on plant products such as fruit, flowers, pollen and nectar.

They are mammals and are members of the Pteropodidae or fruit bat family and have the largest body size of all bats. If you enjoy scientifically exact names you may like to know that these bats are of the order Chiroptera, which means hand wing.

In Australia, The Grey-headed Megabat (Pteropus poliocephalus) is the largest member of the family. Its wingspan can reach one metre and it can weigh up to one kilogram.

Generally congregate in camps made up of large numbers of individuals, but some also roost singly or in small groups. Camps can be found in a range of vegetation types, usually close to water in an area with a dense under storey.

Many hang low in the trees and are in clear view and often they do not fly away as you approach.

They seem to know how they will be treated in different camps. Thus they will stay to stare back at you if you are quiet. They are not much worried by your voice but the sound of snapping branches or leaves crushing as you walk over them, if you are right in the camp/roost means danger in their language.

If you stay for a while, reasonably still and quiet, they will continue their normal activities while you watch.

Are highly mobile, ranging up to 40 km from their camps at night to feed. And also move up to hundreds of kilometres to follow the flowering and fruiting of their food sources.

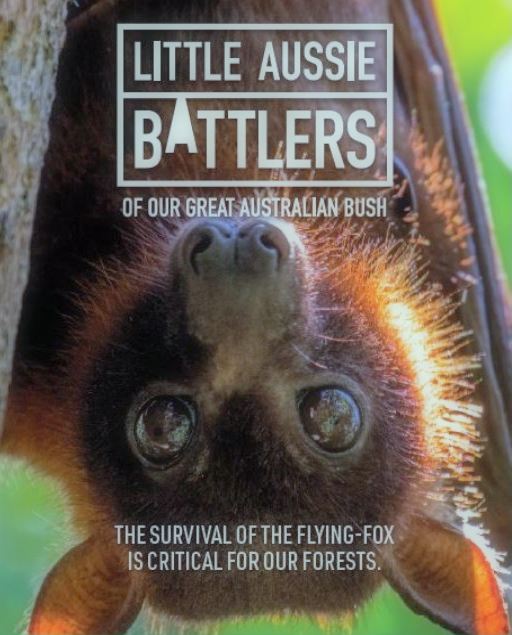

Play a vital role in keeping our ecosystems in good health. Pollinate flowers and disperse seeds as they forage on the nectar and pollen of eucalyptus, melaleucas and banksias and on the fruits of rainforest trees and vines. Are important in ensuring the survival of our threatened rainforests such as the Wet Tropics and Gondwana rainforests, both listed as World Heritage sites.

They are called bats, Megabats, fruit bats and flying-foxes – it’s all the same animal. This is confusing because they are no relation to foxes, fruit is not usually their main food, and they are very different from other members of the bat family. The bat family can be divided approximately into two groups: the Megabats and Microbats (the little ones that are talked about in stories from Europe and USA). Megabats do not occur naturally in Europe or USA, so all those spooky bat stories have nothing to do with our Megabats.

The Megabat, contrary to its name, is not always large: the smallest species is 6 centimetres (2.4 in) long and thus smaller than some Microbats. (see pics below and the following links for Blossom Bat).

There are four species native to mainland Australia: Little Red (Pteropus Scapulatus), Black (Pteropus Alecto), Spectacled (Pteropus conspicillatus) and Grey-headed (Pteropus poliocephalus).

They do not have the ability to echolocate (produce ultrasonic pulses originating in the larynx) like all Microbats. (with one exception, the Egyptian fruit bat Rousettus egyptiacus, which uses high-pitched clicks to navigate in caves). Instead, they rely on their well-developed eyesight which are highly adapted for day and night vision and particularly suited to recognising colours at night. Colour recognition is important for flying-foxes when searching for food. and a sense of smell to locate food.

Megabats are phytophagous - feeding primarily on ripe fruit, but also floral resources (pollen and nectar), bark, seeds and leaves. This makes them important pollinators and long-distance dispersers of tropical plants.

Megabats are frugivorous or nectarivorous, i.e., they eat fruits or lick nectar from flowers. Often the fruits are crushed and only the juices consumed. The teeth are adapted to bite through hard fruit skins. Large fruit bats must land in order to eat fruit, while the smaller species are able to hover with flapping wings in front of a flower or fruit.

Frugivorous bats aid the distribution of plants (and therefore, forests) by carrying the fruits with them and spitting the seeds or eliminating them elsewhere. Nectarivores actually pollinate visited plants. They bear long tongues that are inserted deep into the flower; pollen thereby passed to the bat is then transported to the next blossom visited, pollinating it. This relationship between plants and bats is a form of mutualism known as chiropterophily. Examples of plants that benefit from this arrangement include the baobabs of the genus Adansonia and the sausage tree (Kigelia).

Bats are usually thought to belong to one of two monophyletic groups, a view that is reflected in their classification into two suborders (Megachiroptera and Microchiroptera). According to this hypothesis, all living megabats and microbats are descendants of a common ancestor species that was already capable of flight.

However, there have been other views, and a vigorous debate persists to this date. For example, in the 1980s and 1990s, some researchers proposed (based primarily on the similarity of the visual pathways) that the Megachiroptera were in fact more closely affiliated with the primates than the Microchiroptera, with the two groups of bats having therefore evolved flight via convergence. However, a recent flurry of genetic studies confirms the more longstanding notion that all bats are indeed members of the same clade, the Chiroptera. Other studies have recently suggested that certain families of microbats (possibly the horseshoe bats, mouse-tailed bats and the false vampires) are evolutionarily closer to the fruit bats than to other microbats.

EYESIGHT

You can expect them to take a great deal of interest in you, and stare a lot with their big bright eyes. Their daytime eyesight is about as good as yours, and in the dark they see very much better than you do. up to 20 times.

Megabats are frugivorous or nectarivorous, i.e., they eat fruits or lick nectar from flowers. Often the fruits are crushed and only the juices consumed. The teeth are adapted to bite through hard fruit skins. Large fruit bats must land in order to eat fruit, while the smaller species are able to hover with flapping wings in front of a flower or fruit.

Frugivorous bats aid the distribution of plants (and therefore, forests) by carrying the fruits with them and spitting the seeds or eliminating them elsewhere. Nectarivores actually pollinate visited plants. They bear long tongues that are inserted deep into the flower; pollen thereby passed to the bat is then transported to the next blossom visited, pollinating it. This relationship between plants and bats is a form of mutualism known as chiropterophily. Examples of plants that benefit from this arrangement include the baobabs of the genus Adansonia and the sausage tree (Kigelia).

Bats are usually thought to belong to one of two monophyletic groups, a view that is reflected in their classification into two suborders (Megachiroptera and Microchiroptera). According to this hypothesis, all living megabats and microbats are descendants of a common ancestor species that was already capable of flight.

However, there have been other views, and a vigorous debate persists to this date. For example, in the 1980s and 1990s, some researchers proposed (based primarily on the similarity of the visual pathways) that the Megachiroptera were in fact more closely affiliated with the primates than the Microchiroptera, with the two groups of bats having therefore evolved flight via convergence. However, a recent flurry of genetic studies confirms the more longstanding notion that all bats are indeed members of the same clade, the Chiroptera. Other studies have recently suggested that certain families of microbats (possibly the horseshoe bats, mouse-tailed bats and the false vampires) are evolutionarily closer to the fruit bats than to other microbats.

EYESIGHT

You can expect them to take a great deal of interest in you, and stare a lot with their big bright eyes. Their daytime eyesight is about as good as yours, and in the dark they see very much better than you do. up to 20 times.

WHY THEY DON’T STAND UP

And of course they will be hanging from their feet, head downwards. Their legs are like strong cords, with no bulky muscles, so they cannot stand. Such muscles would make them too heavy for flight. Birds are made lighter by having hollow bones, but Megabats are mammals, and mammals have solid bones.

And of course they will be hanging from their feet, head downwards. Their legs are like strong cords, with no bulky muscles, so they cannot stand. Such muscles would make them too heavy for flight. Birds are made lighter by having hollow bones, but Megabats are mammals, and mammals have solid bones.

THEY ARE OUR COUSINS

They are mammals and from October to April you see them suckling their young. They do this until the baby is five or six months old, but this time varies - they are intelligent and complex so there are differences amongst them, just as there are amongst humans. In fact they are so biologically close to us that they could be classed as primates. We could regard them as close cousins, as we do monkeys.

They are mammals and from October to April you see them suckling their young. They do this until the baby is five or six months old, but this time varies - they are intelligent and complex so there are differences amongst them, just as there are amongst humans. In fact they are so biologically close to us that they could be classed as primates. We could regard them as close cousins, as we do monkeys.

THEY LIKE TO KEEP CLEAN

They groom frequently, licking and combing. Also, of course they are far too clever to dirty themselves with poo or pee.

They groom frequently, licking and combing. Also, of course they are far too clever to dirty themselves with poo or pee.

BUSY DAYS BUT NIGHT TIME IS FOR EATING

Daytime is surprisingly busy for these animals that we usually think of as creatures of the night. You will see them fanning their wings to keep cool when it is hot, grooming, giving birth, tending young, mating, looking around, even flying around: all during daytime. However they will not be eating. When there is a food shortage, they will eat leaves during the daytime in the camp. The camp is the base from which they make their night time foraging trips. They prefer nectar and pollen of native trees and rain forest fruits.Where we have cleared away their native forests they are forced to resort to trees that humans plant for their own use. Records show that appearances of Megabats in orchards coincide with times when bee keepers report poor availability of blossom in the forests. But they are animals which take opportunities – they enjoy the native shrubs and trees that we plant in our gardens.

BABIES

Most babies are born in mid October after about six months gestation. Their eyes are open and alert and they are covered in fur (except for their belly which is bare so they can get closer to mother’s warmth). Baby is ready to find its way to mother’s nipple.

Baby will been born while mother is hanging head downwards as usual but her wings make a safe hammock until baby grasps the nipple with its teeth and mother’s belly fur with its feet.The mother will carry baby with her constantly for the first few weeks. When baby can keep itself warm she will leave baby in the camp at night. She leaves baby in the spot where she has been roosting all day unless there has been danger in the area such as a lurking goanna. During the day she will carry baby around when she makes short flights within the camp, but she can also carry them long distances, even when they are two or three months old. She needs to be able to do this because she needs to be able to move to wherever food can be found. She will carry her baby to the next camp, then the next and the next, and can do this from the first night after the baby is born til the time when the baby can fly well enough to feed itself. This will be later in January, at least. It is particularly enjoyable in late December and in January to watch the babies around the edges of the camp at dusk, practicing their flying.

NOMADS

Megabats follow food supplies. So if we have large numbers, it is because local forests are in blossom with good food. They can move great distances in short times. From 10km up to 100km in a night. One known Megabat had traveled from Sydney to Melbourne in one week.The animals typically move from one traditional campsite to the next. They appear to have long memories for these traditional sites and may even have their own territory in each one that they visit. The females move about more than the males, generally.

HEADING FOR EXTINCTION

In 2001, Grey-headed Megabats were classified as vulnerable by both the federal and New South Wales Government. Regular counts have shown that there are less than five hundred thousand Greys in existence and showed that the population dropped by 30% between 1990 and 2000.The population will always be limited by the food supply in their habitat, and we are constantly clearing their habitat because we like to live in the same places. Loss of habitat is glaringly obvious in the New South Wales and Queensland coastal strips where there has been huge human settlement.The fact that Megabats are slow breeders, producing only one baby each year is not primarily relevant to the survival of the species because the habitat is the limiting factor. No matter how many babies are produced in a year only the number that can be fed in their habitat will survive. If you want to do something towards survival of the species, plant native feed trees.

BATS DRINKING IN THE RIVER

At dusk, after a hot day with no rain, Megabats drink in the river before they fly out for their night of foraging. The hotter the weather is, and the longer the time since there has been rain, the larger the number of Megabats that will be drinking. As the heat of the weather rises to extreme levels Megabats come out earlier and earlier before dusk. When the heat is at dangerous levels the animals will be out in full daylight.First, the Megabats gather in the trees along the riverside, then they may fly up and down the stretch of river several times before they swoop to skim the water. White sprays of water spurt up, then the animal flaps its wings and rises, with its belly fur full of water.When the weather is very hot they often snatch a mouth full of water from their fur as they rise, but all of them fly to a tree nearby to lick their fur thoroughly.They may skim a second time, to collect a second drink. Some clever ones save themselves the effort of skimming and lick at other animals who land dripping nearby. It must take energy and skill to skim and rise again successfully. Youngsters can be seen making beginner efforts, perhaps managing only to dip their feet and flutter tentatively. In events of dangerous heat debilitated animals are not always successful in rising from the water. When they fall in they can swim, with a stroke that looks just like butterfly. Megabats also routinely drink by licking dew from leaves.

WE NEED BATS

Without them our forests would sicken and die.Many Australian hardwood trees are sensitive to inbreeding. For healthy propagation they need to be fertilised by creatures that travel great distances during their feeding, as Megabats do. And the trees release their nectar at night, neatly organised, when Megabats feed. Birds and insects do not have long-range ability in spreading pollen, and smaller creatures are less able to spread seed over long distances than are large flying mammals. Megabats services become more and more valuable as we clear more and more forest, leaving only far- scattered pockets. They are necessary to connect up these remnants.In fact we must have Megabats in large numbers. To make them do their forest work there must be so many that competition forces them to travel widely, pollinating and spreading seed as they feed.When dealing with difficulties that arise from the presence of Megabats it must be kept in mind that they are essential animals in this part of Australia, doing essential forest work that we would not be able to do ourselves even with expenditure of millions of dollars. Without them we would not have forests as we know them, and would lose commercial hardwood varieties of trees in particular. But we would lose more than the forests. We would also lose the animals that depend on these forests, such as koalas and countless other species.In earlier times the animals had a choice of several campsites. They could use areas in turn, allowing each area times for regrowth of worn trees. The alternative sites have now been cleared for farming.Bats can stay at a camps for months, years or tens of years. Moving on to another camp and not return to the recent camp for months, years or tens of years. Clearing has also impacted where bats can roost. Thus they may be packed more tightly than they might choose and cause heavier wear on the trees.Due to these changes made by humans, the vegetation gets regrettably hard wear. however these trees are adapted to such wear and are not killed by it. Locals worry about damage to the vegetation but it is weeds and storms combined that do the worst damage to existing trees, choking and breaking them, and uprooting them completely.Before the mid eighties it was official policy to treat Megabats as a pest species and to try to remove them. Shooting was encouraged and even subsidised. The local council spent money on noise-making equipment in an attempt to scare the bats away. These efforts were ineffective and also were strongly opposed by many people in the community.In 1985 policy disturbance stopped. Many people recognized the essential part that the Megabats play in the forest – for Australian hardwood species they are more important for survival than the birds and the bees. In 2001 both the state and the federal government's listed Grey-headed Megabat as vulnerable.

Counts of grey-headed flying-foxes conducted in 1989 and 1998-2001 indicated a 30 per cent decline in the national population. This qualified the species for listing as a vulnerable species under national environmental law.

Counts of spectacled flying-fox conducted between 1998 and 2000 indicated the spectacled flying-fox population declined from 153,000 in 1998 to about 80,000 in 1999 and 2000. Modelling identified that the species was likely to be extinct in less than 100 years due to the high levels of death associated with human interactions. This made them eligible for listing as vulnerable under national environmental law.

It is important to remember that state governments, irrelevant of a national listing status, consider all species of mega bats to be protected species.

Substantial penalties of up to $5.5 million or up to seven years imprisonment apply for undertaking an activity, to which the EPBC Act applies, without approval. For more information about what this national protection means please refer to:

At some state government levels it is an offence to kill or injure flying-foxes, or to interfere with their camps. If you are proposing the above you are advised to check your obligations under state legislation before undertaking any activities that may kill or injure flying-foxes or interfere with camps.

A recovery plan for the grey-headed flying-fox is being prepared.

The following state and territory government websites also have information on the ecology and biology of flying-foxes:

Activities that are likely to have a significant impact on a nationally threatened species need to be referred to the Australian Government to ensure they are consistent with national environment law. This may include proposals to disperse flying-fox colonies of a nationally threatened species, move or shift camp boundaries, or clearance of important roosting or foraging habitat for a nationally threatened species.

Some activities to manage problematic flying-fox camps may be considered unlikely to have a significant impact and may not need to be submitted to the Australian Government for approval. Examples may include minor modifications to habitat, such as creating buffers by trimming or removing vegetation using appropriate timing and methodology, planting non-roost plant species, or re-vegetating key areas to improve or create additional habitat away from affected areas.

Measures can also be implemented to deter colonies from establishing in inappropriate areas by using noise and visual methods. However, once a camp is established at a site, disturbance using noise and visual methods may result in a significant impact and would require a referral to the Australian Government.

It is recommended that you seek advice from the department before undertaking major habitat modifications or other activities.

To help inform the public about how to live with flying-foxes, the New South Wales, Queensland and Victorian Governments have developed internet sites which may help to answer any questions you have.

The Victorian Department of Sustainability and Environment (DSE) is the only organisation to have undertaken a dispersal of flying-foxes in Australia which has resulted in the total abandonment of the camp from the original location and the establishment of a new camp at a new location in suitable habitat.

The DSE undertook a dispersal of the Royal Botanic Gardens Melbourne camp in 2003 which resulted in the colony moving to the nearby Yarra Bend Park in Kew and to an existing camp in Geelong.

In 2011, DSEWPaC considered a referral from DSE for the 'nudging' (the use of disturbance measures to manage / shift camp boundaries, rather than a dispersal) of the Yarra Bend camp in order to address public concerns with the impacts of this camp on nearby residents.

A Standard Operating Procedure has been developed for these activities that balances the interests of residents with the protection of the grey-headed flying-fox. This includes mitigation measures such as stop-work triggers, no-go zones, various monitoring and reporting protocols and specifications around the timing of the nudging activities to ensure that the breeding cycle of the species is not disrupted.

The Royal Botanic Gardens Melbourne dispersal illustrates the ongoing and adaptive nature of dispersals and highlights the difficulty in defining what actually can be considered a success. The dispersal of flying-foxes from the Royal Botanic Gardens Melbourne resolved the problems around impacting upon heritage values.

However it has raised new issues to be managed, including local resident concerns at the new Yarra Bend location. Cost is also a factor - the Royal Botanic Gardens Melbourne dispersal required thousands of person-hours of effort and approximately $3 million in expenditure.

There is still much to be learnt about how to manage flying-fox dispersals so that they are successful. Monitoring currently forms an important component of dispersal guidelines being developed by DSEWPaC in conjunction with species experts.

FAMILY PTEROPODIDAE

BABIES

Most babies are born in mid October after about six months gestation. Their eyes are open and alert and they are covered in fur (except for their belly which is bare so they can get closer to mother’s warmth). Baby is ready to find its way to mother’s nipple.

Baby will been born while mother is hanging head downwards as usual but her wings make a safe hammock until baby grasps the nipple with its teeth and mother’s belly fur with its feet.The mother will carry baby with her constantly for the first few weeks. When baby can keep itself warm she will leave baby in the camp at night. She leaves baby in the spot where she has been roosting all day unless there has been danger in the area such as a lurking goanna. During the day she will carry baby around when she makes short flights within the camp, but she can also carry them long distances, even when they are two or three months old. She needs to be able to do this because she needs to be able to move to wherever food can be found. She will carry her baby to the next camp, then the next and the next, and can do this from the first night after the baby is born til the time when the baby can fly well enough to feed itself. This will be later in January, at least. It is particularly enjoyable in late December and in January to watch the babies around the edges of the camp at dusk, practicing their flying.

- Bats have sex all year round but only produce one baby in April.

- They mate hanging upside down.

- The strong smell of Megabats is not caused by bat droppings. It comes from an odour the males secrete from glands when they are competing with each-other for females and roosting sites. The smell can be overpowering when tens of thousands of bats roost together in the one colony.

- Each baby has an individual smell which the mother uses to locate it.

- Megabats can live for up to 20 years.

- Megabats have at least 20 different calls which are used for communication

NOMADS

Megabats follow food supplies. So if we have large numbers, it is because local forests are in blossom with good food. They can move great distances in short times. From 10km up to 100km in a night. One known Megabat had traveled from Sydney to Melbourne in one week.The animals typically move from one traditional campsite to the next. They appear to have long memories for these traditional sites and may even have their own territory in each one that they visit. The females move about more than the males, generally.

HEADING FOR EXTINCTION

In 2001, Grey-headed Megabats were classified as vulnerable by both the federal and New South Wales Government. Regular counts have shown that there are less than five hundred thousand Greys in existence and showed that the population dropped by 30% between 1990 and 2000.The population will always be limited by the food supply in their habitat, and we are constantly clearing their habitat because we like to live in the same places. Loss of habitat is glaringly obvious in the New South Wales and Queensland coastal strips where there has been huge human settlement.The fact that Megabats are slow breeders, producing only one baby each year is not primarily relevant to the survival of the species because the habitat is the limiting factor. No matter how many babies are produced in a year only the number that can be fed in their habitat will survive. If you want to do something towards survival of the species, plant native feed trees.

BATS DRINKING IN THE RIVER

At dusk, after a hot day with no rain, Megabats drink in the river before they fly out for their night of foraging. The hotter the weather is, and the longer the time since there has been rain, the larger the number of Megabats that will be drinking. As the heat of the weather rises to extreme levels Megabats come out earlier and earlier before dusk. When the heat is at dangerous levels the animals will be out in full daylight.First, the Megabats gather in the trees along the riverside, then they may fly up and down the stretch of river several times before they swoop to skim the water. White sprays of water spurt up, then the animal flaps its wings and rises, with its belly fur full of water.When the weather is very hot they often snatch a mouth full of water from their fur as they rise, but all of them fly to a tree nearby to lick their fur thoroughly.They may skim a second time, to collect a second drink. Some clever ones save themselves the effort of skimming and lick at other animals who land dripping nearby. It must take energy and skill to skim and rise again successfully. Youngsters can be seen making beginner efforts, perhaps managing only to dip their feet and flutter tentatively. In events of dangerous heat debilitated animals are not always successful in rising from the water. When they fall in they can swim, with a stroke that looks just like butterfly. Megabats also routinely drink by licking dew from leaves.

WE NEED BATS

Without them our forests would sicken and die.Many Australian hardwood trees are sensitive to inbreeding. For healthy propagation they need to be fertilised by creatures that travel great distances during their feeding, as Megabats do. And the trees release their nectar at night, neatly organised, when Megabats feed. Birds and insects do not have long-range ability in spreading pollen, and smaller creatures are less able to spread seed over long distances than are large flying mammals. Megabats services become more and more valuable as we clear more and more forest, leaving only far- scattered pockets. They are necessary to connect up these remnants.In fact we must have Megabats in large numbers. To make them do their forest work there must be so many that competition forces them to travel widely, pollinating and spreading seed as they feed.When dealing with difficulties that arise from the presence of Megabats it must be kept in mind that they are essential animals in this part of Australia, doing essential forest work that we would not be able to do ourselves even with expenditure of millions of dollars. Without them we would not have forests as we know them, and would lose commercial hardwood varieties of trees in particular. But we would lose more than the forests. We would also lose the animals that depend on these forests, such as koalas and countless other species.In earlier times the animals had a choice of several campsites. They could use areas in turn, allowing each area times for regrowth of worn trees. The alternative sites have now been cleared for farming.Bats can stay at a camps for months, years or tens of years. Moving on to another camp and not return to the recent camp for months, years or tens of years. Clearing has also impacted where bats can roost. Thus they may be packed more tightly than they might choose and cause heavier wear on the trees.Due to these changes made by humans, the vegetation gets regrettably hard wear. however these trees are adapted to such wear and are not killed by it. Locals worry about damage to the vegetation but it is weeds and storms combined that do the worst damage to existing trees, choking and breaking them, and uprooting them completely.Before the mid eighties it was official policy to treat Megabats as a pest species and to try to remove them. Shooting was encouraged and even subsidised. The local council spent money on noise-making equipment in an attempt to scare the bats away. These efforts were ineffective and also were strongly opposed by many people in the community.In 1985 policy disturbance stopped. Many people recognized the essential part that the Megabats play in the forest – for Australian hardwood species they are more important for survival than the birds and the bees. In 2001 both the state and the federal government's listed Grey-headed Megabat as vulnerable.

Why are some flying-foxes nationally protected?

The grey-headed flying-fox (Pteropus poliocephalus) and spectacled flying foxes (Pteropus conspicillatus subsp. conspicillatus) are listed under national environmental law (Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999, the EPBC Act). The numbers of Grey-headed and spectacled flying-foxes have declined significantly over recent times, often as a result of habitat clearance caused by human development.Counts of grey-headed flying-foxes conducted in 1989 and 1998-2001 indicated a 30 per cent decline in the national population. This qualified the species for listing as a vulnerable species under national environmental law.

Counts of spectacled flying-fox conducted between 1998 and 2000 indicated the spectacled flying-fox population declined from 153,000 in 1998 to about 80,000 in 1999 and 2000. Modelling identified that the species was likely to be extinct in less than 100 years due to the high levels of death associated with human interactions. This made them eligible for listing as vulnerable under national environmental law.

It is important to remember that state governments, irrelevant of a national listing status, consider all species of mega bats to be protected species.

What does this national protection mean?

Activities likely to have a significant impact on the grey-headed or spectacled flying-fox must be referred to the Australian Government. If you are not sure if a proposed activity is likely to have a significant impact on these megabats, please contact the department to discuss it by emailing epbc.referrals@environment.gov.au or phoning 1800 803 772.Substantial penalties of up to $5.5 million or up to seven years imprisonment apply for undertaking an activity, to which the EPBC Act applies, without approval. For more information about what this national protection means please refer to:

At some state government levels it is an offence to kill or injure flying-foxes, or to interfere with their camps. If you are proposing the above you are advised to check your obligations under state legislation before undertaking any activities that may kill or injure flying-foxes or interfere with camps.

Where can I get more information on flying-foxes?

Further information on the nationally listed grey-headed and spectacled flying-foxes can be found in the Species Profiles and Threats database (SPRAT profiles) for these species. There is also a national recovery plan in place for the spectacled flying-fox, containing details of the species' biology, threats and recovery objectives.A recovery plan for the grey-headed flying-fox is being prepared.

The following state and territory government websites also have information on the ecology and biology of flying-foxes:

- Queensland Department of Environment and Resource Management - A-Z of animals

- New South Wales Department of Environment & Heritage - Native Animals - Flying Foxes

- Victoria Department of Sustainability and Environment - Flying foxes

- South AustraliaDepartment of Environment and Natural Resources

- Northern Territory Natural Resources, Environment, the Arts and Sport - Flying Fox (Bat)

How can flying-foxes be managed in accordance with national environmental law?

Flying-fox camps can be large and may occur in trees that are close to houses and livestock. Residents who live near camps often have concerns regarding noise, damage to vegetation and hygiene associated with flying-fox camps.Activities that are likely to have a significant impact on a nationally threatened species need to be referred to the Australian Government to ensure they are consistent with national environment law. This may include proposals to disperse flying-fox colonies of a nationally threatened species, move or shift camp boundaries, or clearance of important roosting or foraging habitat for a nationally threatened species.

Some activities to manage problematic flying-fox camps may be considered unlikely to have a significant impact and may not need to be submitted to the Australian Government for approval. Examples may include minor modifications to habitat, such as creating buffers by trimming or removing vegetation using appropriate timing and methodology, planting non-roost plant species, or re-vegetating key areas to improve or create additional habitat away from affected areas.

Measures can also be implemented to deter colonies from establishing in inappropriate areas by using noise and visual methods. However, once a camp is established at a site, disturbance using noise and visual methods may result in a significant impact and would require a referral to the Australian Government.

It is recommended that you seek advice from the department before undertaking major habitat modifications or other activities.

To help inform the public about how to live with flying-foxes, the New South Wales, Queensland and Victorian Governments have developed internet sites which may help to answer any questions you have.

- NSW Department of Environment & Heritage - Flying-foxes

- Queensland Department of Environment and Resource Management - Flying foxes

- Victoria Department of Sustainability and Environment- Flying foxes

How have problematic flying-fox camps been managed in the past?

Case study: Yarra Bend, VictoriaThe Victorian Department of Sustainability and Environment (DSE) is the only organisation to have undertaken a dispersal of flying-foxes in Australia which has resulted in the total abandonment of the camp from the original location and the establishment of a new camp at a new location in suitable habitat.

The DSE undertook a dispersal of the Royal Botanic Gardens Melbourne camp in 2003 which resulted in the colony moving to the nearby Yarra Bend Park in Kew and to an existing camp in Geelong.

In 2011, DSEWPaC considered a referral from DSE for the 'nudging' (the use of disturbance measures to manage / shift camp boundaries, rather than a dispersal) of the Yarra Bend camp in order to address public concerns with the impacts of this camp on nearby residents.

A Standard Operating Procedure has been developed for these activities that balances the interests of residents with the protection of the grey-headed flying-fox. This includes mitigation measures such as stop-work triggers, no-go zones, various monitoring and reporting protocols and specifications around the timing of the nudging activities to ensure that the breeding cycle of the species is not disrupted.

The Royal Botanic Gardens Melbourne dispersal illustrates the ongoing and adaptive nature of dispersals and highlights the difficulty in defining what actually can be considered a success. The dispersal of flying-foxes from the Royal Botanic Gardens Melbourne resolved the problems around impacting upon heritage values.

However it has raised new issues to be managed, including local resident concerns at the new Yarra Bend location. Cost is also a factor - the Royal Botanic Gardens Melbourne dispersal required thousands of person-hours of effort and approximately $3 million in expenditure.

There is still much to be learnt about how to manage flying-fox dispersals so that they are successful. Monitoring currently forms an important component of dispersal guidelines being developed by DSEWPaC in conjunction with species experts.

List of species

The family Pteropodidae is divided into seven subfamilies with 186 total extant species, represented by 44 - 46 genera:FAMILY PTEROPODIDAE

- Subfamily Nyctimeninae

- Genus Nyctimene - tube-nosed fruit bats

- Broad-striped Tube-nosed Fruit Bat, Nyctimene aello

- Common Tube-nosed Fruit Bat, Nyctimene albiventer

- Pallas's Tube-nosed Fruit Bat, Nyctimene cephalotes

- Dark Tube-nosed Fruit Bat, Nyctimene celaeno

- Mountain Tube-nosed Fruit Bat, Nyctimene certans

- Round-eared Tube-nosed Fruit Bat, Nyctimene cyclotis

- Dragon Tube-nosed Fruit Bat, Nyctimene draconilla

- Keast's Tube-nosed Fruit Bat, Nyctimene keasti

- Island Tube-nosed Fruit Bat, Nyctimene major

- Malaita Tube-nosed Fruit Bat, Nyctimene malaitensis

- Demonic Tube-nosed Fruit Bat, Nyctimene masalai

- Lesser Tube-nosed Bat, Nyctimene minutus

- Philippine Tube-nosed Fruit Bat, Nyctimene rabori

- Eastern Tube-nosed Bat, Nyctimene robinsoni

- Nendo Tube-nosed Fruit Bat, Nyctimene sanctacrucis (early 20th century †)

- Umboi Tube-nosed Fruit Bat, Nyctimene vizcaccia

- Genus Paranyctimene

- Lesser Tube-nosed Fruit Bat, Paranyctimene raptor

- Steadfast Tube-nosed Fruit Bat, Paranyctimene tenax

- Genus Nyctimene - tube-nosed fruit bats

- Subfamily Cynopterinae

- Genus Aethalops - pygmy fruit bats

- Borneo Fruit Bat, Aethalops aequalis

- Pygmy Fruit Bat, Aethalops alecto

- Genus Alionycteris

- Mindanao Pygmy Fruit Bat, Alionycteris paucidentata

- Genus Balionycteris

- Spotted-winged Fruit Bat, Balionycteris maculata

- Genus Chironax

- Black-capped Fruit Bat, Chironax melanocephalus

- Genus Cynopterus - dog-faced fruit bats or short-nosed fruit bats

- Lesser Short-nosed Fruit Bat, Cynopterus brachyotis

- Horsfield’s Fruit Bat, Cynopterus horsfieldii

- Peters’s Fruit Bat, Cynopterus luzoniensis

- Minute Fruit Bat, Cynopterus minutus

- Nusatenggara Short-nosed Fruit Bat, Cynopterus nusatenggara

- Greater Short-nosed Fruit Bat, Cynopterus sphinx

- Indonesian Short-nosed Fruit Bat, Cynopterus titthaecheilus

- Genus Dyacopterus - Dayak fruit bats

- Brooks’s Dyak Fruit Bat, Dyacopterus brooksi

- Rickart's Dyak Fruit Bat, Dyacopterus rickarti

- Dayak Fruit Bat, Dyacopterus spadiceus

- Genus Haplonycteris

- Fischer's Pygmy Fruit Bat, Haplonycteris fischeri

- Genus Latidens

- Salim Ali's Fruit Bat, Latidens salimalii

- Genus Megaerops

- Tailless Fruit Bat, Megaerops ecaudatus

- Javan Tailless Fruit Bat, Megaerops kusnotoi

- Ratanaworabhan's Fruit Bat, Megaerops niphanae

- White-collared Fruit Bat, Megaerops wetmorei

- Genus Otopteropus

- Luzon Fruit Bat, Otopteropus cartilagonodus

- Genus Penthetor

- Dusky Fruit Bat, Penthetor lucasi

- Genus Ptenochirus - musky fruit bats

- Greater Musky Fruit Bat, Ptenochirus jagori

- Lesser Musky Fruit Bat, Ptenochirus minor

- Genus Sphaerias

- Blanford's Fruit Bat, Sphaerias blanfordi

- Genus Thoopterus

- Swift Fruit Bat, Thoopterus nigrescens

- Genus Aethalops - pygmy fruit bats

- Subfamily Harpiyonycterinae

- Genus Aproteles

- Bulmer's Fruit Bat, Aproteles bulmerae

- Genus Dobsonia - bare-backed fruit bats

- Andersen's Bare-backed Fruit Bat, Dobsonia anderseni

- Beaufort's Naked-backed Fruit Bat, Dobsonia beauforti

- Philippine Bare-backed Fruit Bat, Dobsonia chapmani

- Halmahera Naked-backed Fruit Bat, Dobsonia crenulata

- Biak Naked-backed Fruit Bat, Dobsonia emersa

- Sulawesi Naked-backed Fruit Bat, Dobsonia exoleta

- Solomon's Naked-backed Fruit Bat, Dobsonia inermis

- Lesser Naked-backed Fruit Bat, Dobsonia minor

- Moluccan Naked-backed Fruit Bat, Dobsonia moluccensis

- Panniet Naked-backed Fruit Bat, Dobsonia pannietensis

- Western Naked-backed Fruit Bat, Dobsonia peroni

- New Britain Naked-backed Fruit Bat, Dobsonia praedatrix

- Greenish Naked-backed Fruit Bat, Dobsonia viridis

- Genus Harpyionycteris

- Sulawesi Harpy Fruit Bat, Harpyionycteris celebensis

- Harpy Fruit Bat, Harpyionycteris whiteheadi

- Genus Aproteles

- Subfamily Macroglossinae

- Genus Macroglossus - long-tongued fruit bats

- Long-tongued Nectar Bat, Macroglossus minimus

- Long-tongued Fruit Bat, Macroglossus sobrinus

- Genus Melonycteris

- Fardoulis' Blossom Bat, Melonycteris fardoulisi

- Black-bellied Fruit Bat, Melonycteris melanops

- Woodford's Fruit Bat, Melonycteris woodfordi

- Genus Notopteris - long-tailed fruit bats

- Long-tailed Fruit Bat, Notopteris macdonaldi (Fiji and Vanuatu)

- New Caledonia Blossom Bat, Notopteris neocaledonica (New Caledonia)

- Genus Syconycteris - blossom bats

- Common Blossom Bat, Syconycteris australis

- Halmahera Blossom Bat, Syconycteris carolinae

- Moss-forest Blossom Bat, Syconycteris hobbit

- Genus Macroglossus - long-tongued fruit bats

- Subfamily Pteropodinae

- Genus Acerodon

- Sulawesi mega bats, Acerodon celebensis

- Talaud mega bats, Acerodon humilis

- Giant Golden-crowned mega bat, Acerodon jubatus

- Palawan Fruit Bat, Acerodon leucotis

- Sunda mega bats, Acerodon mackloti

- Genus Desmalopex

- White-winged mega bats, Desmalopex leucopterus

- Small White-winged mega bats, Desmalopex microleucopterus

- Genus Eidolon - straw-coloured fruit bats

- Madagascan Fruit Bat, Eidolon dupreanum

- Straw-coloured Fruit Bat, Eidolon helvum

- Genus Mirimiri

- Fijian Monkey-faced Bat, Mirimiri acrodonta

- Genus Neopteryx

- Small-toothed Fruit Bat, Neopteryx frosti

- Genus Pteralopex

- Bougainville Monkey-faced Bat, Pteralopex anceps

- Guadalcanal Monkey-faced Bat, Pteralopex atrata

- Greater Monkey-faced Bat, Pteralopex flanneryi

- Montane Monkey-faced Bat, Pteralopex pulchra

- New Georgian Monkey-faced Bat, Pteralopex taki

- Genus Pteropus - mega bats

- P. alecto species group

- Black mega bat, Pteropus alecto

- P. caniceps species group

- Ashy-headed mega bat, Pteropus caniceps

- P. chrysoproctus species group

- Silvery mega bat, Pteropus argentatus

- Moluccan mega bat, Pteropus chrysoproctus

- Makira mega bat, Pteropus cognatus

- Banks mega bat, Pteropus fundatus

- Solomons mega bat, Pteropus rayneri

- Rennell mega bat, Pteropus rennelli

- P. conspicillatus species group

- Spectacled mega bat, Pteropus conspicillatus

- Ceram Fruit Bat, Pteropus ocularis

- P. livingstonii species group

- Aru mega bat, Pteropus aruensis

- Kei mega bat, Pteropus keyensis

- Livingstone's Fruit Bat, Pteropus livingstonii

- Black-bearded mega bat, Pteropus melanopogon

- P. mariannus species group

- Okinawa mega bat, Pteropus loochoensis

- Mariana Fruit Bat, Pteropus mariannus

- Pelew mega bat, Pteropus pelewensis

- Kosrae mega bat, Pteropus ualanus

- Yap mega bat, Pteropus yapensis

- P. melanotus species group

- Black-eared mega bat, Pteropus melanotus

- P. molossinus species group

- Lombok mega bat, Pteropus lombocensis

- Caroline mega bat, Pteropus molossinus

- Rodrigues mega bat, Pteropus rodricensis

- P. neohibernicus species group

- Great mega bat, Pteropus neohibernicus

- P. niger species group

- Aldabra mega bat, Pteropus aldabrensis

- Mauritianmega bat, Pteropus niger

- Madagascan mega bat, Pteropus rufus

- Seychelles Fruit Bat, Pteropus seychellensis

- Pemba mega bat, Pteropus voeltzkowi

- P. personatus species group

- Bismark Masked mega bat, Pteropus capistratus

- Maskedmega bat, Pteropus personatus

- Temminck's mega bat, Pteropus temminckii

- P. poliocephalus species group

- Big-eared mega bat, Pteropus macrotis

- Geelvink Bay mega bat, Pteropus pohlei

- Grey-headed mega bat, Pteropus poliocephalus

- P. pselaphon species group

- Chuuk mega bat, Pteropus insularis

- Temotu mega bat, Pteropus nitendiensis

- Large Palau mega bat, Pteropus pilosus (19th century †)

- Bonin mega bat, Pteropus pselaphon

- Guam mega bat, Pteropus tokudae (1970s †)

- Insularmega bat, Pteropus tonganus

- Vanikoro mega bat, Pteropus tuberculatus

- New Caledonia mega bat, Pteropus vetulus

- P. samoensis species group

- Vanuatu mega bat, Pteropus anetianus

- Samoa mega bat, Pteropus samoensis

- P. scapulatus species group

- Gilliard's mega bat, Pteropus gilliardorum

- Lesser mega bat, Pteropus mahaganus

- Little Red mega bat, Pteropus scapulatus

- Dwarf mega bat, Pteropus woodfordi

- P. subniger species group

- Admiralty mega bat, Pteropus admiralitatum

- Dusky mega bat, Pteropus brunneus (19th century †)

- Ryukyu mega bat, Pteropus dasymallus

- Nicobar mega bat, Pteropus faunulus

- Gray mega bat, Pteropus griseus

- Ontong Java mega bat, Pteropus howensis

- Small mega bat, Pteropus hypomelanus

- Ornate mega bat, Pteropus ornatus

- Little Golden-mantled mega bat, Pteropus pumilus

- Philippine Gray mega bat, Pteropus speciosus

- Small Mauritian mega bat, Pteropus subniger (19th century †)

- P. vampyrus species group

- Indian mega bat, Pteropus giganteus

- Andersen's mega bat, Pteropus intermedius

- Lyle's mega bat, Pteropus lylei

- Large mega bat, Pteropus vampyrus

- incertae sedis

- Small Samoan mega bat, Pteropus allenorum (19th century †)

- Large Samoan mega bat, Pteropus coxi (19th century †)

- P. alecto species group

- Genus Styloctenium

- Mindoro Stripe-faced Fruit Bat, Styloctenium mindorensis

- Sulawesi Stripe-faced Fruit Bat, Styloctenium wallacei

- Genus Acerodon

- Subfamily Rousettinae

- Genus Eonycteris - dawn fruit bats

- Greater Nectar Bat, Eonycteris major

- Cave Nectar Bat, Eonycteris spelaea

- Philippine Dawn Bat, Eonycteris robusta

- Genus Rousettus - rousette fruit bats

- Subgenus Boneia

- Manado Fruit Bat, Rousettus (Boneia) bidens

- Subgenus Rousettus

- Geoffroy's Rousette, Rousettus amplexicaudatus

- Sulawesi Rousette, Rousettus celebensis

- Egyptian Rousette (Egyptian Fruit Bat), Rousettus aegyptiacus

- Leschenault's Rousette, Rousettus leschenaulti

- Linduan Rousette, Rousettus linduensis

- Comoro Rousette, Rousettus obliviosus

- Bare-backed Rousette, Rousettus spinalatus

- Subgenus Stenonycteris

- Long-haired Rousette, Rousettus (Stenonycteris) lanosus

- Madagascar Rousette, Rousettus (Stenonycteris) madagascariensis

- Subgenus Boneia

- Genus Eonycteris - dawn fruit bats

- Tribe Epomophorini

- Genus Epomophorus - epauletted fruit bats

- Angolan Epauletted Fruit Bat, Epomophorus angolensis

- Ansell's Epauletted Fruit Bat, Epomophorus anselli

- Peters's Epauletted Fruit Bat, Epomophorus crypturus

- Gambian Epauletted Fruit Bat, Epomophorus gambianus

- Lesser Angolan Epauletted Fruit Bat, Epomophorus grandis

- Ethiopian Epauletted Fruit Bat, Epomophorus labiatus

- East African Epauletted Fruit Bat, Epomophorus minimus

- Minor Epauletted Fruit Bat, Epomophorus minor

- Wahlberg's Epauletted Fruit Bat, Epomophorus wahlbergi

- Genus Epomops - epauletted bats

- Buettikofer's Epauletted Fruit Bat, Epomops buettikoferi

- Dobson's Fruit Bat, Epomops dobsoni

- Franquet's Epauletted Fruit Bat, Epomops franqueti

- Genus Hypsignathus

- Hammer-headed Bat, Hypsignathus monstrosus

- Genus Micropteropus - dwarf epauletted bats

- Hayman's Dwarf Epauletted Fruit Bat, Micropteropus intermedius

- Peter's Dwarf Epauletted Fruit Bat, Micropteropus pusillus

- Genus Nanonycteris

- Veldkamp's Dwarf Epauletted Fruit Bat, Nanonycteris veldkampii

- Genus Epomophorus - epauletted fruit bats

- Tribe Myonycterini

- Genus Lissonycteris

- Angolan Rousette, Lissonycteris angolensis

- Genus Megaloglossus

- Woermann's Bat, Megaloglossus woermanni

- Genus Myonycteris - little collared fruit bats

- São Tomé Collared Fruit Bat, Myonycteris brachycephala

- East African Little Collared Fruit Bat, Myonycteris relicta

- Little Collared Fruit Bat, Myonycteris torquata

- Genus Lissonycteris

- Tribe Plerotini

- Genus Plerotes

- D'Anchieta's Fruit Bat, Plerotes anchietae

- Genus Plerotes

- Tribe Scotonycterini

- Genus Casinycteris

- Short-palated Fruit Bat, Casinycteris argynnis

- Genus Scotonycteris

- Zenker's Fruit Bat, Scotonycteris zenkeri

- Pohle's Fruit Bat, Scotonycteris ophiodon

- Genus Casinycteris

COMMENTS